- Home

- Olivia Gaines

Blind Hope Page 3

Blind Hope Read online

Page 3

“You don’t need to tell me that,” Judy said.

“You’re right, I’m sorry,” Miles apologized. “I’m curious though, Judy, what do you want to be when you grow up? You gon’ be like yo’ Mama, or you gonna be better?”

“I’m going to be better,” she said. “My child will have a home. A permanent one.”

“I see,” Miles said, saying no more.

She liked Miles. He was a stand-up guy. One of the last semi-decent ones, but Princess, being herself, became jealous of his relationship with Judy. Although several times Judy tried to explain to her mother that he treated her like a daughter, Princess didn’t want to hear it.

“Your fucking father didn’t treat you like a daughter,” Princess said. “You never trust men, Judy! Never. They get close to use you. Once you are used up, they discard you like trash. It’s best to get them before they get you.”

She was 16 when they arrived at the bus station in Atlanta, a bustling town filled with movers and shakers and well-dressed Black people. She had never seen so many affluent African Americans in her life who drove nice cars, had nice homes, and went to work every day to jobs at offices in tall buildings. Gerald, her mother’s latest mark, had one of those jobs and two cars. Princess didn’t drive and the Atlanta traffic was too much for the woman. She wouldn’t allow Gerald to teach Judy to drive either.

The life with Gerald ended when Princess came home early and found him in bed with another man. He asked her to join them in the party, which sent Princess into a rage. The police came at Gerald’s insistence because Princess was attempting to castrate him.

Judy never wanted to leave Atlanta, but thanks to Gerald’s connections, and Princess’ insistence on going to the media to out his down low lifestyle, he set her up with a sweet gig in Chicago. The gig even came with her own apartment. However, it didn’t take Princess long to hook up with Clem, who had bad news written all over him.

“Mama, there’s something wrong with that man,” Judy said. “His eyes aren’t right. The thinking is wrong. That man freaks me out.”

“Child, ain’t I taught you nothing?” Princess asked.

“Yes, you taught me to follow my instincts and never trust a man,” Judy said. “I’m telling you I don’t trust him. We have a good thing. You’re paying your own rent, making a decent wage. This is the one time we don’t need a man to survive.”

“Baby, it’s about more than just surviving,” Princess said. “In the middle of the night, when it’s just you and your man, there is a sweet spot of connection that you’ll understand one day.”

The day didn’t come. At 18 years old, Judy came home to find her mother dead, a deep red gash from one ear to the other, displaying Princess’s throat being cut from one end to another. Her mother’s wallet was gone and the bank account empty. Luckily for them both, her mother’s account was butter and egg money. The main account was in Judy’s name as an insurance policy. It wasn’t the only policy Judy kept. Using money from her part-time job, she had taken out a life insurance policy on Princess, paying $10 a month to ensure that when the time came, life wouldn’t leave her as Cinderella’s work shoes. The apartment would be missed, but Clem would not.

Clem was nowhere to be found, but sticking to what her mother taught, she took only the small tokens of their life in Chicago. Princess’s nice jewelry pieces that would get pawned in lean times went in her backpack. A photo of she and her mother as well as one of Judy and Miles were the only items that were of personal value to her. The apartment meant nothing. Although it had been their only permanent home since she was 10, whoever killed her mother could come back to get her. She wasn’t waiting for that to happen.

Saying farewell to her mother with a modest cremation service, she loaded her one suitcase and took a bus to New York. Before she left, she notified the insurance company of the passing of her mother and her forwarding PO Box in Brooklyn at a UPS Store. The nice boss at her part-time job put in a reference for Judy in New York, saying she was good worker ensuring the young woman had a job when she got to Brooklyn.

For three years, she worked her ass off, saving as much as she could in the rainy-day account and put in for a transfer to Atlantic City where she met Robert, a cute young man with no real ambition other than to be a rapper.

She asked one night as she lay close to him, “What about a home? A family? A yard for the dog and kids to run in with fresh air?”

“Naw, that ain’t the life for me. I’m a city boy. I’m an action junkie,” Robert told her.

She appreciated his honesty, but it wasn’t what she wanted in life. For too long, she’d had nothing and the last thing she needed was a man who wanted short term gains and flashing lights. Princess lived under flashing lights on stage, creating an illusion of a woman going places who moved often, but never got anywhere. It wouldn’t be Judy’s life.

There were no buses in the walking away from Robert, just a nice note that read, “We want different things.” She would miss the nights the sweet spot of connection her mother had talked about. But a girl couldn’t eat connection, although Robert did a helluva job eating the sweet spot. She deserved more and she would get it.

At the age of 23, Atlantic City had been good to her. Using the card counting trick taught to her by Miles, she made a small fortune, squirreling it away like a chipmunk in winter. Her new boss said he was heading to Vegas to manage a new casino.

“I could use a sharp cookie like you, Judy,” he told her. “I need a man on the inside that I can trust, and you are just the man for the job.”

“Will you provide room and board, plus an airline ticket to Las Vegas?”

“Sure doll,” Jimmy the Flint told her.

Two weeks later, she was on her way to Las Vegas, working at a casino in the Freemont experience. This is where she met one Caleb Morrow, a man with a vision. The sweet spot at night consisted of watching DIY television of people living off the grid.

“We could get us a nice piece of land in Missouri, raise some crops, get a living roof, and some solar panels allowing the sun to provide all the power we could ever need,” Caleb told her.

Initially she thought he was lying, but on her first vacation, an actual vacation where there were plans to go on a trip and come home, he took her to Missouri. A little plot of land he’d said, turned out to be 20 acres of the most beautiful corner of America she’d ever seen in her life. In a rented Winnebago, parked next to Moniteau Creek, she consented to be his wife. Two years later, as new parents, living in a home they had slaved over and built themselves, she gave birth to their child, Johnnie, a sweet kid who rarely cried and made a doting Momma smile.

Life was good but money was low. Raising crops yielded year-round food, but Caleb wasn’t a hunter, which meant no meat. He bought a second used car that needed a fuel pump and an alternator, which he promised to work on and teach her to drive. The same broken-down car sat in the front yard by the broken-down fence a year later.

“Judy, I got a call from Jimmy the Flint,” Caleb said one night. Johnnie was four at the time. “He’s got some work he needs me to do.”

“Caleb, you know Jimmy. That’s why they call him the Flint. He’s sharp but is good at starting fires,” she stated firmly. “We have a good life here. If you go to Jimmy, you won’t come back the same if you get back at all. Get a job in town.”

But Caleb wasn’t a nine to five kind of man. In her heart she knew it was only a matter of time, which is why she never told him about the bank account which she saved for a rainy day. It was nearly $75,000 strong when he left that cold October morning. A year later he hadn’t returned. The insurance policy she’d taken out on him had a double indemnity clause. If he died by accidental death, the payout would be grand and she would have enough to put Johnnie through college. She waved goodbye to him on a Monday morning as he took the working car, his old suitcase and the smile which had gotten her into his bed. Promising to call later in the week, she didn’t look back as he drove out

the yard.

Although he called each Sunday, his voice seemed strained. One Sunday, she heard a woman’s voice in the background, and Judy knew her husband wasn’t coming home. Never one to be religious, she wasn’t going to take up with another man, being married to one already. She did the next best thing – made a call to Jimmy the Flint.

“Accidents usually run around 50,000,” he told.

“I wonder if it can be a remote location, where the accident takes a while to allow the blood to run out of his lying heart,” she said as twirled a lock of her hair.

“I’ll send you a number,” Jimmy said, clicking off the line.

No matter how hard she tried to not be her mother, it seemed that every two years she needed to move. Only now, her lungs filled with fluid, her child nearly starved, and no way to leave the house, money in the bank meant nothing to a woman with no internet and no phone. Uncertain if her husband was alive or dead, her soul ached from the pain of failing, to give Johnnie better than she had and a man in the child’s life to love and guide the wee sprout into adulthood so her baby wouldn’t become the line of faces from her childhood who shared a bed in order to have a roof over its head.

She and Johnnie hid from the men who came looking for Caleb. More than likely, he’d taken something from them and they wanted it back. Unbeknownst to her, the slimeball had taken money from her as well. The secret account wasn’t so secret. The remaining twenty-five grand in the account, he’d accessed and siphoned off, leaving she and Johnnie with nothing. With no proof of his death, she couldn’t get the insurance money.

The stupid car in the front yard Caleb never fixed for her to even practice at driving, and the town of Rocheport was a good 25 miles away. She couldn’t make it in winter with a small child. As much as she wanted to pray for help, it would have been hypocritical to do so, all things considered. Instead, Caleb sent help to them.

Cotter was handsome man, who didn’t say much, but worked hard to make sure they ate and she got better. Each day she was stronger, and today, she was on her feet. Weak. Coughing. Still a bit feverish but she was up. Moving would give her strength that she would need to make life go forward. She’d made coffee for them and oatmeal for breakfast, sitting across the table from the man, wrapped in his blanket as Johnnie enjoyed 30 minutes of morning cartoons.

“I never left because this is our home, plus I can’t drive, and Caleb took all my money,” she confessed.

“Gathered as much,” Cotter said, listening to the wet cough. Urging her back to the couch after breakfast with a cup of hot tea, he asked her permission to take Johnnie to town to get a coat and decent pair of boots. She knew pedophiles and men with dark hearts. Cotter didn’t have one, but Johnnie had been taught, just as Princess had taught her, to say the right things to stay safe. She let him leave with the child. Trust was all she had. A gnawing feeling inside of her said Cotter wouldn’t leave her here to die.

When the man returned, he also brought with him a fold-a-way bed to sleep on in the living room. It seemed he planned to stay awhile. There was a darkness around his soul that stood out like an aura of death attached to him. At this point, if he were Death himself, Judy didn’t care. She preferred the Devil who was nursing her back to health versus the one who was going to come calling again, looking for whatever Caleb took.

Life was hard. It was tougher if you were a dumb thief. Her husband was the dumbest of the lot. Yet, she was grateful to him for sending help. Maybe, he hadn’t been so stupid after all.

Chapter Four – Well, I’ll Be Damned

Johnnie sat in the backseat of the truck, strapped in and gazing out the window as if they’d just driven into Disneyland. Since the woman didn’t drive and Caleb had been gone a while, it was obvious the child hadn’t left the homestead. It tugged at the aortic strings around his hardened heart that a sweet kid could get such a rotten deal. The mom didn’t seem so bad, but she married a man like Caleb Morrow. In his estimation, that meant she wasn’t that good either.

“Hey kid, when was the last time you’ve seen your old man?” Cotter asked, looking in the rear-view mirror.

“It’s been a while,” Johnnie said. “I think it was at my birthday. Momma made me a cake with four candles on it. Daddy was home then. Haven’t seen him since.”

“You miss your old man?”

“Not really,” Johnnie said. “Mama says you can’t miss what you never really had. She was talking about meat, but I know she meant Daddy.”

Cotter looked again in the rear-view mirror at the boy. Scrawny. However, the eyes held a spark and the kid was no dummy. He seemed to pick up on everything said and unsaid. It amused him that the child knew just what to say when asked a question. Never giving away too much, but telling him just what he wanted to know.

“I don’t know what size you are, so I hope you don’t mind us going to the second-hand store to get you some clothes,” Cotter said. “The way you’re eating, I can see you tripling in size in no time.”

“Second hand? You mean like used clothes?” Johnnie asked.

“Yeah, is that a problem?”

“No, Mama always went to the Goodwill when Daddy took us to town to shop,” Johnnie said. “She never bought used underwear though. Or used shoes. Said she didn’t want me getting a foot rash from somebody else’s dirty toes.”

“Smart,” Cotter said.

“Yeah, Mama is really smart. She taught me to read, write my name, and do math too.”

“You don’t go to school?”

“I just turned six,” Johnnie said. “I think she said in the fall, I would start first grade. She’s been working with me to make sure I won't be behind the other kids when I do. The car should be fixed by then, so she can drive me to the bus stop.”

“Good to know,” Cotter said, slowing his speed as he drove through Rocheport, connecting to Highway Bb, and then the interstate.

“Where are we going?” Johnnie asked, looking out the window.

“Columbia, they have more stores,” Cotter said. “I need to get a few more things that are cheaper in a bigger town.”

“If I had some money, I would get Mama something pretty to make her feel better,” Johnnie said pausing. “Mister, can I have a few dollars to get her a present. I will work hard to pay you back.”

“I tell you what, Johnnie, I will give you $10 and we will call it an allowance,” Cotter said, “for all the help you’ve given me with your Mama and the house.”

“An allowance? Cool!” Johnnie said pleased. “Do I get that every week or every month? I have to know so I can make a budget.”

Cotter burst into laughter. The kid was growing on him. A bit too much for his comfort, but in every life, there needed to be hope. If there was nothing else, he could give him or his mother before it left, it would be hope. At this point, most of what he offered was a blind hope, because he couldn’t for the life of him see it going anywhere, but he was here. So, were they, in the pile of poo together − for now, anyway? In a week or two the woman would be well and he’d be gone on his way. A great deal needed to be done before he left, and staying busy was always a plus.

THE GPS GUIDED HIM to the Salvation Army Family Store where the first item he looked for was a heavy winter coat. Finding one he liked, that had a zip out lining, it wasn’t very pleasing to Johnnie who didn’t like the color. The kid wanted one in bright orange that looked more like a hunting jacket.

“You sure that’s the one you want?” Cotter asked in disbelief.

“I like how bright it is,” Johnnie said, locating a pair of matching neon orange socks with the price tag still attached. “Mister Cotter, this pair is new. Nobody’s toes have been in these.”

He frowned as a saleswoman came over to offer them help. Cotter went down a list of sweaters, long sleeve shirts, and pants that was needed for the growing kid. Since he didn’t know the kid’s size, the lady offered him assistance.

“I need one for show and one to grow,” he said, echoing the words of hi

s mother when she would shop for him as boy. It didn’t matter how big the size of a shirt she bought, in less than two months, Cotter seemed to outgrow the material. Johnnie looked as if he would do the same.

Four pairs of jeans, two pairs of pants, and a shirt, which looked more like a salmon colored blouse lay in the cart. A brand-new pair of snow boots, minus a previous pair of owner’s feet, were added to the buggy, along with two sweaters, a Kermit the Frog sweatshirt, and four long sleeve shirts. Satisfied, Johnnie, in the neon orange socks, matching coat, and new boots, climbed into the back seat, happy as a lark.

“I’m hungry,” the kid said.

“Kinda figured,” Cotter replied. “Whaddaya want to eat?”

“Don’t know,” Johnnie said. “Am I buying my food out of my allowance or is it your treat?”

Cotter laughed again. He was really starting to like the kid a great deal. He drove the two of them to Wal-Mart, which had a Burger King inside. To his surprise, Johnnie didn’t want french fries but opted instead for apple slices. He inquired as to why.

“Those fries taste funny,” Johnnie offered. “My Mama makes the best fries from real potatoes. Those don’t taste real. The chicken nuggets are good though.”

“Leave it to me to get stuck with a kid with a refined palate,” Cotter mumbled as they ate in silence. Johnnie’s eyes followed the young girls with their mothers, taking note of the clothing they wore and hairstyles.

“What are we getting in here, Mister Cotter?”

“Undies, soap, washing powder, that kind of stuff,” Cotter said.

“Good, I need a new toothbrush,” Johnnie said. “Mine looks like a cartoon character with bad hair.”

Cotter found himself laughing again. Bright. Imaginative. The kid had a good imagination even after nearly freezing to death in that hovel of a handmade house. His hand went to his chest to stop the rush of feeling around his heart.

Cutting it Close

Cutting it Close Maple Sundaes & CIder Donuts

Maple Sundaes & CIder Donuts Holden

Holden Oregon Trails

Oregon Trails Blind Date (Venture, Georgia Book 3)

Blind Date (Venture, Georgia Book 3) On a Rainy Night in Georgia

On a Rainy Night in Georgia My Thursday Throwback

My Thursday Throwback The Bento Box

The Bento Box A Menu For Loving

A Menu For Loving Thursdays in Savannah

Thursdays in Savannah Blind Hope (The Technicians Book 2)

Blind Hope (The Technicians Book 2) North to Alaska

North to Alaska Becoming the Czar

Becoming the Czar A Weekend with the Cromwells

A Weekend with the Cromwells The Tennessee Mountain Man

The Tennessee Mountain Man Blind Date

Blind Date Blind Fate

Blind Fate Dancing with Mr. Blakemore

Dancing with Mr. Blakemore Friends with Benefits

Friends with Benefits A Walk Through Endurance

A Walk Through Endurance Lunchtime Chronicles: A Yummy Sub

Lunchtime Chronicles: A Yummy Sub Bleu, Grass, Bourbon

Bleu, Grass, Bourbon The Christmas Quilts

The Christmas Quilts Turning the Page

Turning the Page Blind Hope

Blind Hope Killers

Killers Blind Luck (The Technicians Series Book 3)

Blind Luck (The Technicians Series Book 3) Blind Copy (The Technicians Series Book 5)

Blind Copy (The Technicians Series Book 5) Santa's Big Helper

Santa's Big Helper A Frickin' Fantastic Friday (The Zelda Dairies Book 3)

A Frickin' Fantastic Friday (The Zelda Dairies Book 3) Cruising with the Blakemores

Cruising with the Blakemores Being Mr. Blakemore (The Blakemore Files Book 7)

Being Mr. Blakemore (The Blakemore Files Book 7) Welcome to Serenity

Welcome to Serenity Shopping with Mrs. Blakemore

Shopping with Mrs. Blakemore Vanity's Pleasure

Vanity's Pleasure Loving the Czar (The Blakemore Files Book 6)

Loving the Czar (The Blakemore Files Book 6) Montana (Modern Mail Order Bride Book 2)

Montana (Modern Mail Order Bride Book 2) Courting Guinevere (The Davonshire Series Book 1)

Courting Guinevere (The Davonshire Series Book 1) A Tantalizing Tuesday (The Zelda Diaries Book 2)

A Tantalizing Tuesday (The Zelda Diaries Book 2) A Saucy Sunday (The Zelda Diaries Book 4)

A Saucy Sunday (The Zelda Diaries Book 4) Being Mrs. Blakemore

Being Mrs. Blakemore The Brute & The Blogger

The Brute & The Blogger it Happened Last Wednesday (The Zelda Diaries Book 1)

it Happened Last Wednesday (The Zelda Diaries Book 1) A Weekend with the Blakemores (The Blakemore Files Book 8)

A Weekend with the Blakemores (The Blakemore Files Book 8) Buckeye and the Babe

Buckeye and the Babe Dinner With the Blakemores (The Blakemore Files Book 5)

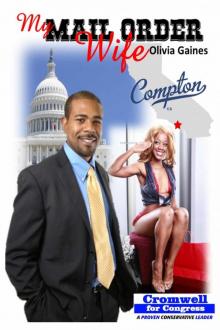

Dinner With the Blakemores (The Blakemore Files Book 5) My Mail Order Wife (The Value of a Man Book 1)

My Mail Order Wife (The Value of a Man Book 1)